Table of Contents

Art museums- are more than mere collections of paintings and sculptures. They are sanctuaries of human expression, temples of imagination, and chronicles of history. Within their hallowed halls reside works that transcend aesthetic admiration. These pieces possess the uncanny power to evoke awe, contemplation, and revelation. They whisper forgotten tales, ignite creative passions, and connect disparate eras through the language of form and color.

In the realm of visual storytelling, art museums serve as both vaults of beauty and vessels of secret knowledge. Behind the polished frames and spotlit sculptures lie mysteries—some ancient, some modern, all extraordinary. Each piece tells more than what meets the eye. Each brushstroke, chisel mark, and material choice speaks volumes. To walk through a museum is to walk through the psyche of civilization itself.

Here are ten incredible pieces from art museums around the world that will absolutely blow your mind, each revealing a unique secret or stirring truth waiting to be discovered.

1.The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger (1533)

A Masterpiece of Symbolism, Diplomacy, and Memento Mori

The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger (1533) stands as one of the most intellectually layered and visually arresting works of Renaissance portraiture. This grand double portrait, executed with painstaking precision and masterful illusionism, immortalizes Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve—two French diplomats stationed in Tudor England—against a background teeming with allegorical instruments and encoded meaning.

At first glance, the painting dazzles with its opulence. Rich textures—silken fabrics, fur-lined garments, and polished wood—exude aristocratic gravitas. Yet beneath the surface lies a labyrinth of symbology, a veritable visual sermon on knowledge, mortality, and the fractured nature of the early 16th-century world. Holbein, a court painter to Henry VIII and a genius of Northern Renaissance realism, imbues The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger (1533) with an esoteric complexity that continues to captivate scholars and aesthetes alike.

The objects arrayed on the shelves between the figures serve as clues to the painting’s deeper commentary. A celestial globe, a lute with a broken string, and various scientific instruments all point to the intellectual and cosmological turmoil of the Reformation era. The lute, traditionally a symbol of harmony, speaks volumes through its damage—suggesting religious discord and ideological rupture.

Yet the painting’s most arresting element is the anamorphic skull that sprawls diagonally across the floor. When viewed from the correct oblique angle, it resolves into a chilling memento mori, reminding viewers that all worldly knowledge and earthly grandeur are ultimately transient. This optical tour de force serves not merely as a technical marvel, but as a philosophical anchor to the work’s moral gravity.

Holbein’s treatment of space and perspective in The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger (1533) demonstrates a profound command of humanist ideals. Each element—whether the terrestrial globe, the hymnbook, or the quadrant—emphasizes the Renaissance pursuit of empirical knowledge and cosmopolitan diplomacy. And yet, through the skewed skull and somber tones, he also injects an unsettling awareness of death’s inevitability.

Color plays a crucial role in heightening the narrative. The subdued background curtain provides contrast for the luminous attire of the ambassadors, while the metallic luster of the instruments gives the canvas a sense of both prestige and impermanence. The subtle chiaroscuro modeling enhances the three-dimensionality, guiding the eye with an almost architectural precision.

Ultimately, The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger (1533) operates on multiple strata—political, philosophical, spiritual. It is both a celebration of Renaissance intellect and a sobering meditation on mortality. In one canvas, Holbein has captured the fragility of human endeavor against the immutable passage of time. The result is not merely a portrait, but a portal into the ideological and existential anxieties of a world on the brink of transformation.

2.The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch (1490–1510)

A Surreal Vision of Paradise, Sin, and Damnation

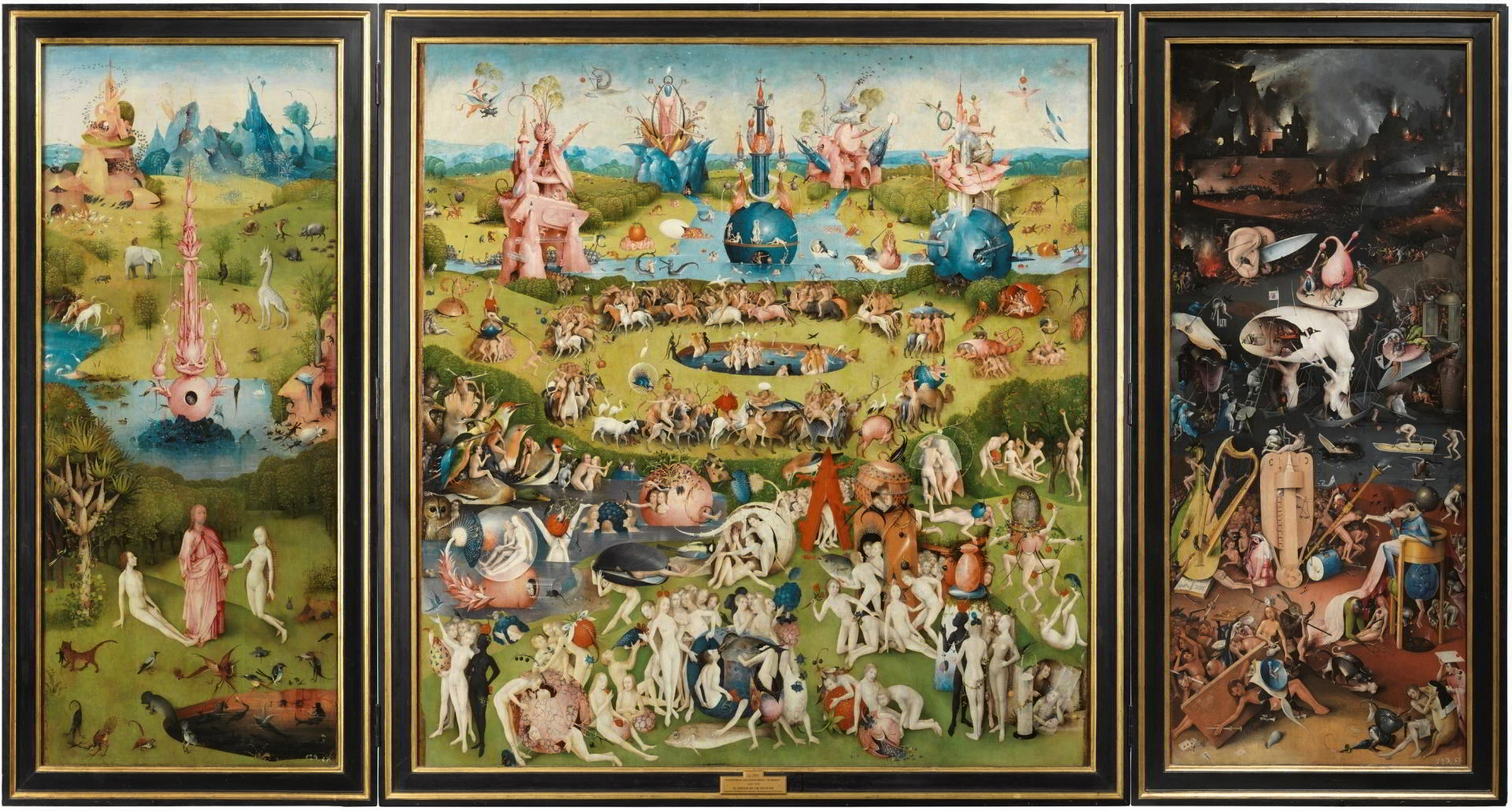

The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch (1490–1510) stands as one of the most enigmatic and surreal masterpieces in the history of Western art. This triptych, believed to have been painted during the transition from the Late Gothic to the Northern Renaissance, shatters traditional iconography with a phantasmagoric display of allegory, fantasy, and moral inquiry. Bosch’s fantastical imagination transcends the confines of his era, offering a complex, visual exegesis on human desire and its consequences.

The closed panels, painted in monochrome grisaille, depict the world on the third day of Creation—an austere, unpopulated globe presided over by a distant and watchful Creator. Yet, once opened, the triptych erupts into a kaleidoscopic tableau teeming with hybrid creatures, impossible architectures, and uncanny juxtapositions. The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch (1490–1510) becomes a hallucinatory theatre of human folly, delight, and inevitable ruin.

The left panel, a paradisiacal Eden, introduces Adam and Eve under the benign gaze of Christ. However, even here, the seeds of temptation are subtly sown. Strange animals—some invented, some symbolic—foreshadow the dissonance to come. The central panel, from which the painting draws its title, is a dense tapestry of carnal revelry. Naked figures frolic amidst oversized fruits, birds, and aqueous landscapes. The imagery is both idyllic and grotesque, a visual paradox teetering between ecstasy and absurdity.

This middle section has often provoked intense scholarly debate. Is it a depiction of prelapsarian innocence or a damning indictment of hedonism? The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch (1490–1510) resists linear interpretation. The sensuous chaos may reflect humanity’s insatiable appetite for pleasure, or perhaps it reveals a cautionary tale masked in fantastical charm. Bosch’s ambiguity is deliberate, encouraging contemplation rather than conclusion.

The right panel plunges into a nightmarish hellscape—a grotesque inversion of the central panel’s pleasures. Here, Bosch’s ingenuity turns macabre. Torture, despair, and surreal punishments abound. Musical instruments become instruments of torment; faces are distorted in agony. A colossal, hollowed-out figure with an egg-shaped torso, often dubbed the “Tree-Man,” surveys the ruin with haunting resignation. Fire, darkness, and mutilation permeate every corner of this infernal domain.

The entire composition is rendered with meticulous detail and technical dexterity. Bosch’s palette ranges from luminous pastels to brooding shadows, capturing both ethereal beauty and horrific decay. His brushwork, though subtle, is precise—each figure and symbol calibrated for maximum psychological and symbolic impact.

In essence, The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch (1490–1510) is a profound visual sermon. It traverses the arc of human experience—from divine origin through sensual indulgence to spiritual desolation. Unflinching and visionary, Bosch’s magnum opus remains an enduring mirror to our desires, our delusions, and the price we pay for paradise pursued without wisdom.

3.Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez (1656)

A Baroque Enigma of Power, Perception, and Presence

Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez (1656) is a masterwork that defies conventional categorization. At once a royal portrait, a meta-painting, and a philosophical meditation on the act of seeing, this vast canvas—housed in Madrid’s Museo del Prado—anchors Velázquez’s reputation as a genius of Baroque complexity. It is not merely an artwork, but an enduring conundrum that continues to provoke fascination and scholarly discourse.

The scene unfolds within the painter’s own studio at the Alcázar palace. Central to the composition is the Infanta Margarita Teresa, surrounded by her entourage of ladies-in-waiting (las meninas), a dwarf, a mastiff, and various courtiers. At first glance, it appears to be a depiction of courtly routine. Yet, nothing in Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez (1656) is as straightforward as it seems.

Velázquez inserts himself into the scene, standing before a large canvas, brush in hand. This self-insertion shatters the traditional boundary between artist and subject. Behind him, a mirror reflects the king and queen—Philip IV and Mariana of Austria—implying their presence outside the painted frame, perhaps where the viewer now stands. This visual sleight of hand elevates the painting from portraiture to an ontological inquiry into art’s relationship with reality.

The spatial arrangement is equally audacious. Light flows from an unseen window to the right, illuminating the Infanta and casting subtle shadows that infuse the room with dimensional depth. The vanishing point converges on a doorway at the back of the room, where a courtier exits or enters—frozen in liminal ambiguity. Through such techniques, Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez (1656) transforms linear perspective into a dramatic tool for directing perception and focus.

Every figure is rendered with acute psychological presence. The Infanta’s aristocratic poise contrasts with the informal attentiveness of her maids. The dwarf gazes outward with a look that blends fatigue and defiance, while Velázquez himself appears contemplative, perhaps challenging the viewer to consider who truly commands the gaze. The mirror—often interpreted as a portal between dimensions—suggests a recursive relationship between viewer, subject, and artist. Are we the ones being observed?

Technically, Velázquez demonstrates consummate mastery. His brushwork, while restrained, achieves a velvety luminosity that animates fabric, flesh, and atmosphere with naturalistic veracity. Yet he avoids rigid clarity. Instead, he hints at detail, trusting the eye to assemble the illusion—a technique that prefigures impressionist sensibilities centuries later.

Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez (1656) is not content to depict; it interrogates. It questions hierarchy, authorship, and the fluid boundary between observer and observed. In the act of painting royalty, Velázquez elevates the role of the artist to that of intellectual and courtier, a bold assertion in an age governed by rigid social stratification.

In its layered meanings and hypnotic ambiguity, this painting stands as a testament to the power of visual art to transcend time, provoke thought, and inhabit the interstice between reality and illusion. Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez (1656) remains one of the most intellectually charged and visually commanding achievements in Western art.

4.The Water Lilies by Claude Monet (1914–1926)

An Immersive Meditation in Color, Light, and Transcendence

The Water Lilies by Claude Monet (1914–1926) is not merely a series of paintings—it is a visual symphony that transcends representation, transporting the viewer into a liminal world suspended between reality and reverie. Created during the final decades of Monet’s life at his garden in Giverny, these monumental works dissolve form into color, drawing the eye into a realm where time seems to evaporate and the self becomes absorbed in pure sensation.

The series, composed of nearly 250 paintings, explores a single motif: Monet’s water lily pond. Yet through shifting light, ephemeral reflections, and chromatic nuance, each canvas becomes utterly unique. The Water Lilies by Claude Monet (1914–1926) are less depictions of flora and more metaphysical inquiries into perception and presence. They abandon traditional perspective, rejecting fixed vantage points in favor of an enveloping, almost cosmic horizontality.

This late period in Monet’s oeuvre coincided with failing eyesight due to cataracts, which paradoxically contributed to the ethereal abstraction that defines these works. Blurred outlines, smudged transitions, and vaporous colors suggest not deterioration but liberation—a detachment from physical precision in pursuit of emotional truth. Some canvases span meters in width, immersing the viewer in an uninterrupted field of pulsating blues, pinks, violets, and jade.

In The Water Lilies by Claude Monet (1914–1926), sky and water commingle. The reflective surface of the pond serves as a mirror to the heavens, as trees and clouds shimmer across the water’s skin. It is difficult to determine what lies above and what belongs below. This ambiguity is not accidental; it is deliberate, a conscious dissolution of boundaries that positions nature not as static subject but as fluid phenomenon.

Monet painted en plein air but reworked much of the series within the studio, allowing memory and emotion to guide his palette and gesture. The brushstrokes vary from short, stippled touches to sweeping arcs that echo the motion of wind across water. This painterly tactility invites not only visual but tactile engagement. The viewer does not simply look at The Water Lilies by Claude Monet (1914–1926)—one enters them.

A number of these masterpieces now reside in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, arranged in two oval rooms designed in collaboration with Monet himself. The result is a space of contemplation, a secular chapel devoted to the spiritual resonance of nature. Here, silence enhances the experience, and the works function less as paintings and more as portals to a heightened state of awareness.

The Water Lilies by Claude Monet (1914–1926) culminate a lifelong pursuit of capturing the ephemeral. They are meditations on impermanence and beauty, serenity and flux. In an age fractured by war and industrialization, Monet’s water lilies offer an oasis—a visual balm whispering of harmony, continuity, and the quiet profundity of the natural world.

5. The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault (1819)

Occupying a massive wall in the Louvre, The Raft of the Medusa is not merely a depiction of shipwreck survivors. It is a political indictment, a psychological portrait, and a technical marvel. Géricault, only in his twenties when he painted it, based the piece on a real tragedy involving a French frigate.

The figures—emaciated, desperate, hopeful—are portrayed with raw emotional intensity. Géricault interviewed survivors, studied corpses, and created detailed sketches to achieve his vision. The triangular composition leads the eye upward from despair to hope as one figure waves frantically to a distant ship.

It is a study in human endurance and governmental failure, resonating across time as a testament to both horror and hope.

6. The Night Watch by Rembrandt van Rijn (1642)

In Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, Rembrandt’s The Night Watch stands as a monument to cinematic dynamism and psychological complexity. Though it appears to be a simple militia portrait, the painting pulses with motion, shadow, and symbolic depth.

Rembrandt broke with tradition by depicting the figures in dramatic action rather than static poses. The play of light, the layers of meaning, and the inclusion of a mysterious young girl with a chicken all provoke curiosity. Who is she? Why is she illuminated?

Beyond its technical brilliance, the painting captures the civic pride and chaotic beauty of 17th-century Amsterdam. It’s a canvas that vibrates with life, daring viewers to step into its narrative.

7. The Thinker by Auguste Rodin (1904)

Though many recognize the iconic bronze statue, few realize that The Thinker was originally part of a larger composition: The Gates of Hell. Housed in the Musée Rodin in Paris, this sculpture represents not just contemplation, but inner turmoil.

With muscles tensed and brow furrowed, the figure does not rest but wrestles with existential quandaries. Rodin intended it to represent Dante himself, pondering the scenes of the Inferno. The sculpture’s monumental scale and emotional gravity pull the observer into its psychological tension.

It is not just a statue. It is the embodiment of the human condition.

8. The Kiss by Gustav Klimt (1907–1908)

In the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, Klimt’s golden masterpiece sparkles with sensual elegance and spiritual resonance. The Kiss is a radiant fusion of love, ornamentation, and transcendence. The couple, locked in a tender embrace, are enshrined in a mosaic of shimmering patterns.

Klimt drew from Byzantine iconography, Art Nouveau, and his own introspective depths to create a piece that feels sacred. Every curve and color sings of affection and unity.

It’s a celebration of intimacy that elevates physical connection into something almost divine.

9. Guernica by Pablo Picasso (1937)

Picasso’s massive monochrome mural, displayed in the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, is a visual scream against the horrors of war. Created in response to the bombing of the Spanish town Guernica, this piece explodes with agony, disarray, and symbolism.

Horses, bulls, mothers, and dismembered limbs collide in a fractured composition that mirrors the chaos of violence. Despite its somber tone, the painting holds a rebellious spirit, a refusal to let horror go unchallenged.

It is not simply a condemnation. It is a rallying cry—a piece that shakes the soul awake.

10. Infinity Mirror Rooms by Yayoi Kusama (1965–Present)

Step into a universe of endless reflections in Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms, showcased in various contemporary museums around the world. These immersive installations use mirrors, lights, and space to create a disorienting and ecstatic experience.

Each room invites viewers into a psychedelic cosmos where perception folds upon itself. Kusama, who has battled mental illness throughout her life, infuses each space with vulnerability, transcendence, and radical self-expression.

It’s a marriage of technology and emotion—a postmodern sanctuary that feels both intimate and infinite.